Welcome to Causal Inference!

Introductions, foundational ideas

2024-09-04

Welcome to Causal Inference!

To follow along:

- Open Moodle

- Under Course Resources, click link for our course website

- Under Activities (top menu), click “Introductions and foundational ideas”

Quote of the day:

New goals don’t deliver new results. New lifestyles do. And a lifestyle is a process, not an outcome. For this reason, all of your energy should go into building better habits, not chasing better results.

- James Clear

Building community

Before we start talking about causal inference, we will take time to get to know each other.

Take 5 minutes to have a conversation with the people at your table:

- Introduce yourselves however you see fit.

- What’s something that’s on your mind this fall?

My causal journey

Spring 2016 - Causal Inference in Medicine and Public Health with Dr. Elizabeth Stuart

My causal journey

On the first day, she presented the kinds of questions that we’d be trying to answer:

- Does the Head Start program improve educational and health outcomes for children?

- Does participation in a perinatal depression prevention program improve postpartum mental health?

- By how much do high-level NICU’s reduce infant mortality?

- Does a “healthy marriage” intervention improve relationship quality?

My eyes were big and locked in–in a way that I hadn’t felt in a long time.

(This was actually only my second ever applied statistics course. Every other course I had taken was largely theoretical!)

Should we?

- Does the Head Start program improve educational and health outcomes for children?

- Does participation in a perinatal depression prevention program improve postpartum mental health?

- By how much do high-level NICU’s reduce infant mortality?

- Does a “healthy marriage” intervention improve relationship quality?

Should we?

- Does the Head Start program improve educational and health outcomes for children? Should we continue to fund and run Head Start programs the way they’re currently being implemented?

- For all children? What types of children benefit more or less than others?

- Does participation in a perinatal depression prevention program improve postpartum mental health? Should we increase access to these depression prevention programs for all pregnant individuals?

- For all pregnant individuals? What characteristics of individuals might cause them to benefit more than others?

Causal inference is a quest to make the world a better place.

Trying to do good causal inference brings out the best in us.

It requires collaboration with people of diverse expertise, humility, and slow thinking.

(Speaking of diverse expertise, you all come from a huge variety of backgrounds! Statistics, Economics, Data Science, Biology, Environmental Science, Math, Sociology, Political Science, Chemistry)

Some inspiration

These tools and ideas are the kinds of things that, if you use them right, can turn you from a consumer of knowledge into a producer. You can find the answer to questions nobody else has the answer to. You can figure out how the world really works on your own. I think that’s pretty darn cool!

The Effect - Introduction

Plan for remainder of today

- Let’s take some time to clarify our intuitions and natural inclinations surrounding the idea of causation.

- This will help us develop a core framework for our course.

Reflection: Known causes

Think about some causal relationships that you are sure about—where you can say “I know that ___ causes ___.”

How do you know?

Bradford-Hill criteria

In 1965, the English statistician Sir Austin Bradford Hill proposed 9 criteria for evaluating the evidence for causal relationships:

- Strength: Big associations might be more likely to be causal.

- Consistency: Replicability of the finding across samples and contexts lends support for a causal relationship.

- Specificity: A causal relationship is more likely if there is a very specific population at a specific site and disease with no other likely explanation.

- Temporality: Exposure/treatment happens first, then the outcome.

- Biological gradient: A dose–response relationship. Increasing the amount of exposure should generally lead to a more pronounced effect.

- Plausibility: Being able to explain why. A reported relationship is more plausible if there are reasonable mechanism(s) for the relationship. (Knowledge of the mechanism is limited by current knowledge.)

- Coherence: The coherence between different sources of evidence (e.g., epidemiological and laboratory findings).

- Experiment: Evidence from controlled experiments can be compelling.

- Analogy: The observed association is just like (analogous to) some other association.

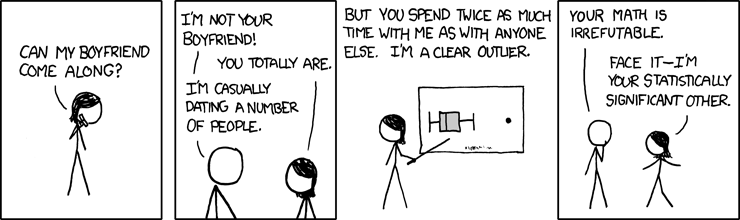

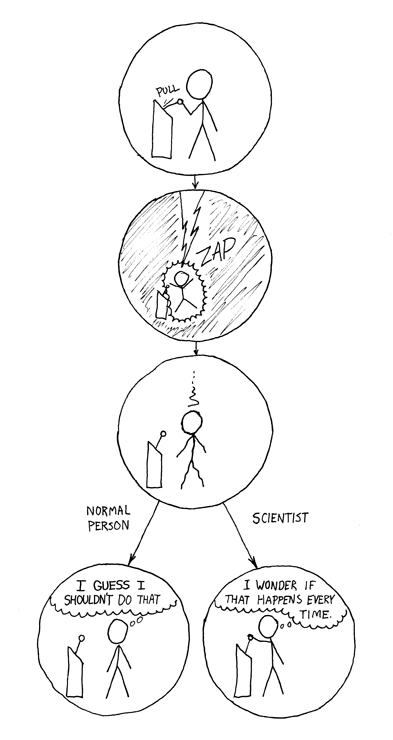

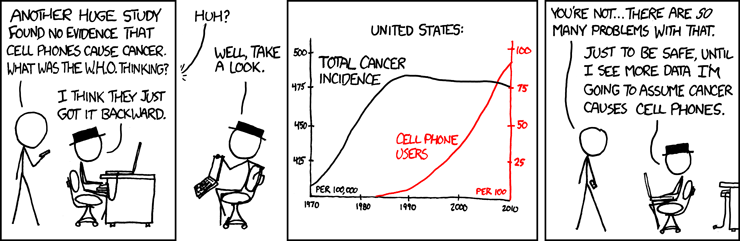

Lucy D’Agostino McGowan at Vanderbilt came up with a great mapping between these criteria and xkcd cartoons–see here for her full talk. I’ll show some of my favorites.

Strength

Consistency

Temporality

What if?

Maybe we are sure about some causes because we really do feel like we know what would have happened if things had somehow been different.

Potential outcomes

The outcomes that would (potentially) result under different scenarios of an exposure or treatment.

- \(A\): Treatment or exposure variable (“A” for action)

- Often binary but doesn’t have to be: \(A = 1\) for treated/exposed. \(A = 0\) for controls/untreated/unexposed

- \(Y\): Observed outcome

- \(Y^a\): Potential outcomes

- \(Y^{a=1}\): Potential outcome under treatment. What the outcome would be if the unit received treatment.

- \(Y^{a=0}\): Potential outcome under control. What the outcome would be if the unit did not receive treatment.

- We can only observe one potential outcome.

- Why? Potential outcomes are the answer to “What if?”

- They are specific to a particular unit and point in time. (e.g., Me on 9/1/2024 at 11:11AM, Minnesota in August 2024)

Potential outcomes in movies

In It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey gets help from his guardian angel Clarence to see how the lives of those close to him would have turned out if he had never been born.

Potential outcomes in movies

In Everything Everywhere All at Once, Evelyn Wang is able get a glimpse of the lives of the people around her under different “incarnations” of herself.

Potential outcomes: Example 1

I’m about to drive to Minneapolis.

- \(A = 1\): Take the highway to Minneapolis

- \(A = 0\): Take city roads to Minneapolis

- \(Y\): Observed commute time (minutes) on Sept 1, 2024 at 5:12PM

- \(Y^{a=1}\): Commute time on Sept 1, 2024 at 5:12PM if taking the highway

- \(Y^{a=0}\): Commute time on Sept 1, 2024 at 5:12PM if taking city roads

I decide to take city roads.

- \(Y = 25\)

- \(Y^{a=0} = 25\)

- Suppose my friend simultaneously heads out and takes the highway and it takes 42 minutes. We have not observed what would have happened if I took the highway, but we are pretty confident that \(Y^{a=1} = 42\).

- The causal effect of taking the highway vs. city roads on Sept 1, 2024 at 5:12PM is an excess commute time of 42-25 = 17 minutes.

Potential outcomes: Example 2

I wake up in the morning with a headache.

- \(A = 1\): Take aspirin for my headache

- \(A = 0\): Do nothing for my headache

- \(Y\): Headache outcome (headache / no headache) on Sept 1, 2024 at 8:34AM

- \(Y^{a=1}\): Headache outcome on on Sept 1, 2024 at 8:34AM if taking aspirin

- \(Y^{a=0}\): Headache outcome on on Sept 1, 2024 at 8:34AM if doing nothing

I take an aspirin.

- \(Y = \text{no headache}\)

- \(Y^{a=1} = \text{no headache}\)

- \(Y^{a=0} = ?\)

- I don’t know if my headache would have gone away on its own.

- Maybe I remember enough about previous headaches to guess that it probably would not have.

- But the guess of \(Y^{a=0} = \text{headache}\) is a guess. Truly \(Y^{a=0}\) is unknowable.

Potential outcomes: Example 3

Colleges are deciding whether to adopt a test-optional admissions policy.

- \(A = 1\): College adopts a test-optional admissions policy

- \(A = 0\): College does not adopt a test-optional admissions policy

- \(Y\): Number of applications for regular decision enrollment for Fall 2024

- \(Y^{a=1}\): # applications under a test-optional admissions policy

- \(Y^{a=0}\): # applications without a test-optional admissions policy

Macalester adopts a test-optional admissions policy in 2020.

- \(Y = 8915\)

- \(Y^{a=1} = 8915\)

- \(Y^{a=0} = ???\)

- Very hard to know how many applicants Mac would have received without the policy.

- But if were to collect a lot of data over time on many colleges, we might be able to learn about average potential outcomes.

Potential outcomes and average causal effects

- The previous examples focused on potential outcomes (POs) for a given unit (an individual, a college).

- Contrasting these POs for a single unit is very interesting but very hard to do with confidence.

- Easier and also useful to contrast POs on average for many (a sample of) units–this is the idea of an average causal effect (ACE).

Potential outcomes across many units

| \(A\) | \(Y^{a=1}\) | \(Y^{a=0}\) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | ? |

| 1 | 0 | ? |

| 1 | 1 | ? |

| 0 | ? | 1 |

| 0 | ? | 1 |

| 0 | ? | 0 |

The fact that there is a ? in every row is known as the fundamental problem of causal inference.

Despite this fundamental problem, we have ways of making good guesses about the missing potential outcomes on average.

Average causal effects

- \(E[Y]\) means expected value of \(Y\)

- This is formally a probability concept, but it has intuition that we can work with.

- It’s a weighted average of the possible values of \(Y\) weighted by how common those values are.

| \(A\) | \(Y^{a=1}\) | \(Y^{a=0}\) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | ? |

| 1 | 0 | ? |

| 1 | 1 | ? |

| 0 | ? | 1 |

| 0 | ? | 1 |

| 0 | ? | 0 |

- One average causal effect is a mean difference:

- \(E[Y^{a=1} - Y^{a=0}] = E[Y^{a=1}] - E[Y^{a=0}]\)

- The expected value of a binary (0/1) variable is the probability that it equals one.

- In this context, mean difference is a probability difference. How much does aspirin change the probability of a headache persisting?

- In the test-optional admissions policy context, mean difference is a difference in the average number of applications. How much does a test optional policy change applicant volume?

Recap and reflection

Let’s take a few minutes to reflect on the ideas of potential outcomes and how we’re defining causal effects. Are these satisfying ways for you to think about causation?

What level will the course be at?

- Waived Probability prereq this semester

- This subject is routinely taught in master’s level programs in public health without probability.

- If you have taken Probability, it can deepen your understanding from a technical/theoretical standpoint.

- Totally possible to use our tools very well to be a producer of knowledge without knowing probability.

What level will the course be at?

In this book I’ll cover what a causal research question even is, and how we can do the hard work of answering that causal research question once we have it.

I’ll do that while scaling far back on equations and proofs. There’s absolutely a technical element to causal inference, and we’ll get to some of that in this book. But when you talk to people who actually do causal research, they think of this stuff intuitively first, not mathematically. They talk about assumptions about the real world and whether they’re reasonable, and what the story is behind the data. After they’ve got that settled, then they worry about equations and statistical properties. Designing good research and proving (or even understanding) statistical theorems are separate tasks. I think they should be introduced in that order.

The Effect - Introduction

Flex Days

I want you to get what you want out of this course.

Given the diversity of our class, a one-size-fits-all approach to what we cover and do in class is not going to work.

Roughly every 1.5 weeks, one class day will be a Flex Day.

- Flex Days are you for to focus on what you need to make the course a success—everyone will be doing something different. (I encourage grouping up to form exploration communities.)

- I’ll provide materials for you to explore that day.

- I’ll do my best to provide a wide variety of materials to explore, but I’ll need you to tell me if what you want to explore is missing.

- General themes for exploration:

- Applications + more examples of the week’s content (like more practice exercises with different data, reading applied research papers)

- Digging into theory / technical details

- Simulation exercises in R

Grading system

- You’ll notice from our syllabus that I have not spelled out a grading system.

- Assignment 1 is a short piece of writing to help me get to know you and move towards deciding on what to do about grading in this course. Due next Wednesday, 9/11.

- Regardless of what we decide for grading, the two main sources of work that receives feedback are (1) the portfolio and (2) the course project.

- Portfolio is built up over weekly assignments (starting week 3). My hope is that it serves as a good reference for you in the future.

For next time

- Check the Schedule for readings from The Effect. (Chapters 1, 2, and 5)

- Readings from The Effect always have video alternatives from the textbook author.

- Update your R and RStudio installations as described here.